Eskay Creek: The Treasure Hunt Continues

Nothing captures the mind of the geologist, investor, or plain-old treasure hunter, quite like high-grade gold (Au). Small wonder that Eskay Creek, once the highest-grade Au mine in the world, has attracted so much attention. Exploration in the area has a fraught history of frustration, failure, partial success, and stunning payoffs for the persistent. Today, 90 years after its discovery, the mine is preparing to enter a new phase of its life, proving that the treasure hunt is far from over.

Eskay Creek

Map showing the location of the Eskay Creek Project.

The Eskay Creek Project is located in northern British Columbia, Canada’s famous Golden Triangle, about 950 km north of Vancouver and 20 km northwest of Newcrest’s Brucejack gold-silver (Au-Ag) mine. It consists of 8 mineral leases, 2 surface leases and several unpatented mining claims totaling 6,151 hectares. The project is 100% owned by Skeena Resources, which purchased the property from Barrick in 2020. Barrick retains a 1% royalty on all claims, with many individual claims also having additional 1-2% royalties owed to various companies and individuals. The mine has all-weather road access and is only 7 km away from the Volcano Creek Hydroelectric Power Station. Skeena expects to have to acquire additional surface rights and water licenses to support the infrastructure necessary to begin mining.

The feasibility study, released in 2022, lists proven mineral reserves of 17.3 Mt at 3.64 g/t Au and 99 g/t Ag, for 4.94 g/t Au equivalent. Probable reserves are 12.6 Mt at 2.1 g/t Au, 50 g/t Ag, for 2.75 g/t Au equivalent. Combined proven and probable reserves stand at 29.9 Mt at 4 g/t Au equivalent. Open pit mineral resources, which include mineral reserves, are 46.5 Mt at 3.5/g/t Au equivalent, with an additional underground resource of 1.3 Mt at 5.7g/t Au equivalent.

The feasibility study calls for production of 352 000 oz/year Au equivalent from an open pit. The project boasts an IRR of 50%, and after tax NPV $ 1.4 billion. Capex is estimated at 592 million Canadian dollars, with construction expected to take approximately 2 years. Mine life is estimated at 9 years.

History

Exploration in the area began in 1932, when a group of three prospectors found a zone of silicified massive sulfides and staked the first claims in the area. Exploration on the property has been nearly continuous since then, however it has been plagued by inconsistent results. Virtually every exploration method imaginable, from prospecting to drilling to geophysics to exploration adits, has been employed at some point, yielding everything from sporadic high-grade Au-Ag to moderate Pb-Zn grades with minimal precious metals, to very little mineralization to speak of. This inconsistency contributed to a revolving door of owners: various areas of the modern Eskay Creek property have been worked by dozens of companies and individuals, most of whom only worked the claims for a few years. At least some valuable information, such as location and results of several geophysics surveys conducted in the 1990’s, has been lost in the course of this game of ‘telephone.’

The 21A and 21B zones, which would eventually become the feedstock of the richest Au mine in the world, were discovered in 1982. It wasn’t until drilling in 1987 that their potential was realized. While in production Eskay Creek was the highest-grade Au mine and fifth-largest Ag producer in the world, producing 3.3 Moz Au and 160 Moz Ag at average grades of 45 g/t Au and 2224 g/t Ag from 1994-2008.

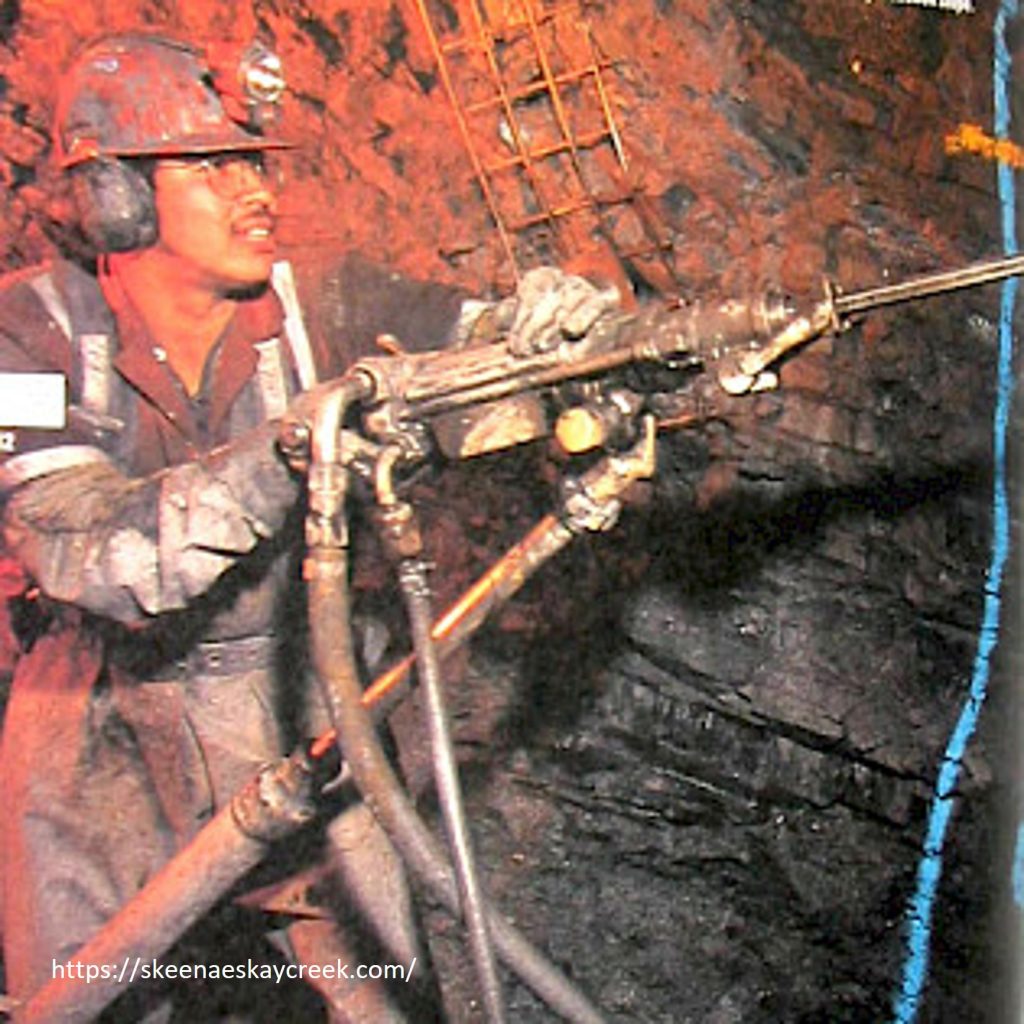

A miner searches for high-grade Au in the old underground Eskay Creek mine.

Extensive drilling and geophysics programs were conducted throughout the 1990s-2000s, but failed to locate significant new mineralization. Very little work was carried out between the mine’s closure and Barrick optioning the project to Skeena in 2017. Since this time Skeena has carried out 10000’s of meters of drilling, leading to the recognition of remaining ore reserves and Skeena acquiring a 100% interest in the property.

Geology

Eskay Creek is hosted within Jurassic-age rocks of the Stikinia Assemblage, along the transition from volcanic rocks of the uppermost Hazelton Group to marine sediments of the Bowser Lake Group. These rocks have been lightly metamorphosed to greenschist facies. Mineralization is stratiform to discordant, and covers an area 1400 m long and as much as 300 m wide. It has been classified into many different zones based on differences in location, Au-Ag grade, mineralogy, and textures. In general, stratiform mineralization is hosted in mudstone sandwiched between volcanic flows, while stockwork and discordant mineralization is hosted in felsic volcanic rocks.

A simplified illustration of the stratigraphy of Eskay Creek.

Gold and silver mainly occur as electrum (Au-Ag alloy), with Ag also occurring in sulfosalts such as barite. Alteration in the underlying volcanic rocks consists of pervasive quartz-sericite-pyrite, potassium-feldspar, chlorite, and silica. Intense alteration is locally accompanied by sulfide-rich veins. The main sulfide minerals are pyrite, sphalerite, galena, and chalcopyrite, although arsenopyrite and mercury-antimony-mercury sulfides are significant in some zones, including the bonanza-grade 21 A and B zones.

Eskay Creek is generally considered a precious metal-rich volcanogenic massive sulfide (VMS) deposit. VMS deposits form on the seafloor near centers of volcanic activity where hot, metal-rich volcanic waters discharge from hydrothermal vents (black smokers). The reaction between the hot volcanic water and cold seawater triggers the dissolved metals to precipitate out, forming a relatively small, but potentially high-grade, mound of massive sulfides with a vein stockwork or breccia zone developed along the vent plumbing system beneath it.

Most VMS deposits are rich in base metals such as zinc, copper, and lead, but typically contain only low grades of gold and silver. Eskay’s extremely high Au and Ag grades and lack of economically significant base metals suggests it’s either an unusual VMS, or something else entirely.

Some have suggested Eskay could be a volcanic hotspring (epithermal) deposit. These form near volcanoes where metal-rich volcanic waters bubble to the surface, cooling and reacting with surrounding rocks to produce Au-Ag rich deposits with lesser base metal sulfides. Epithermal deposits typically consist of vein stockworks and zones of sulfide-rich replacement of host rocks. The (relatively) nearby Brucejack Au-Ag mine is considered an epithermal deposit.

Analysis: A Hard Nut to Crack

With relatively large, high-grade resources, stellar economics, and a relatively short mine-life, Eskay is poised to burn brightly but briefly. The largest obstacle to entering production is likely to be acquiring the required surface rights and water permits.

More broadly, Eskay’s lengthy, complex patchwork of exploration history leaves a lot of uncertainty about its past and future. The feasibility study notes gaps in drilling and underexplored areas, especially more deeply buried volcanic feeders, but it’s anyone’s guess if these are actually mineralized. Eskay has a history of requiring multiple decades of exploration to enable about one decade of (very high-grade) production; clearly, Eskay does not give up its secrets easily.

The entrance to the historic Eskay Creek workings.

Most of the currently defined resources occur very close to the historic workings, in fact the pit will consume many of them. As large and high-grade as they are, they’re little more than the scraps of the historic mine, and they’re only enough to sustain a 9-year mine life. The golden question, then, is how much more is left to be discovered, and where is it?

While Eskay is commonly considered a precious metal-rich VMS, these are typically the result of hydrothermal upgrading during metamorphism or other post-depositional processes. Boliden, Sweden, the most well-known precious metal-rich VMS, is believed to have been upgraded in Au by hydrothermal fluids during extensive, high-grade metamorphism and shearing which transformed many of its original properties. There’s little evidence of such a process operating at Eskay. Furthermore, the fact that Eskay has never produced base metals is extremely unusual for a VMS deposit.

An epithermal/hotspring model would better explain the Au-Ag grades, as well as the presence of electrum and of mercury-antimony-mercury sulfides in some of the highest-grade zones. It would also be more in line with the model of the nearby Brucejack Deposit. On the other hand, the zones of zinc-lead-copper sulfides are more in line with a VMS model, as are the clearly marine volcanic/sedimentary host rocks.

The similarity in ore-forming fluid, depositional environment, and mineralogy between VMS and epithermal models makes it hard to positively distinguish between them, but figuring this out could make a great deal of difference in deciding Eskay’s long term future. Sticking to the VMS model implies that only certain rock layers along the ancient seafloor and underlying feeder structures are prospective, suggesting a narrow, focused exploration program. An epithermal model opens the door to mineralization cutting across stratigraphy and occurring more erratically throughout the area. It’s been nearly 40 years since the discovery of the 21A and B zones; with so little truly new ore discovered since, perhaps it’s time to reevaluate assumptions.

High-grade, pyrite-rich Au-Ag ore in split drillcore.

Investor Takeaways

With a large, high-grade Au-Ag resource and very solid economics, Eskay Creek is poised to become a major producer. The largest short-medium term obstacle to entering production will be acquiring the necessary land and permits. Whether the mine’s short 9-year life can be extended will depend on whether the lingering questions over what type of deposit it is can be resolved, and if new understanding can lead to new discoveries.