Canada’s Critical Minerals Strategy: The First Step on a Long Road

Like many nations today, Canada has committed to developing a stronger domestic supply chain for minerals deemed critical to national security and economic development. Despite big promises many obstacles remain.

Canada’s Critical Minerals Strategy

Critical minerals are broadly defined as mineral resources which are essential for reaching net zero, maintaining national security, and the overall functioning of modern economies, and are also at risk of supply disruptions. The Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy, unveiled late last year, has five core objectives:

- supporting economic growth, competitiveness, and jobs

- climate action and environmental protection

- advancing reconciliation with indigenous peoples

- fostering diverse and inclusive workforces and communities

- enhancing global security and partnerships with allies

These objectives are to be achieved by:

- driving research, innovation, and exploration

- accelerating project development

- building sustainable infrastructure

- advancing reconciliation with indigenous peoples

- growing a diverse workforce and prosperous communities

- strengthening global leadership and security

The infrastructure required to meet net-zero commitments will require vast amounts of critical minerals, which must be sourced largely from new mines.

Although China isn’t explicitly mentioned, there’s little doubt who the ‘competitiveness’ and ‘global security’ language refers to. The beginnings of Canada’s critical minerals strategy traces back to 2011, when China abruptly cut off supplies of rare-earth elements (REEs) to Japan in a move which was widely seen as politically motivated. The disruption, while brief, served as a wakeup call for many developed nations which had become heavily, and in some cases entirely, dependent on importing the raw materials necessary to support a modern economy.

In many cases supply chains of these minerals are dominated by China, which has spent decades quietly cultivating extraction and processing of resources such as REEs, lithium, and cobalt both domestically and abroad. China’s economy has undoubtably reaped the benefits: many essential elements, especially REEs, trade for a substantial discount in China compared to the rest of the world, providing a significant competitive advantage for companies choosing to manufacture everything from cell phones to solar panels to electric vehicles in China. China’s critical minerals strategy has become a pillar of its economy, and, considering their importance to missile/drone guidance systems and other high-tech weapons, could prove a major advantage any future conflict.

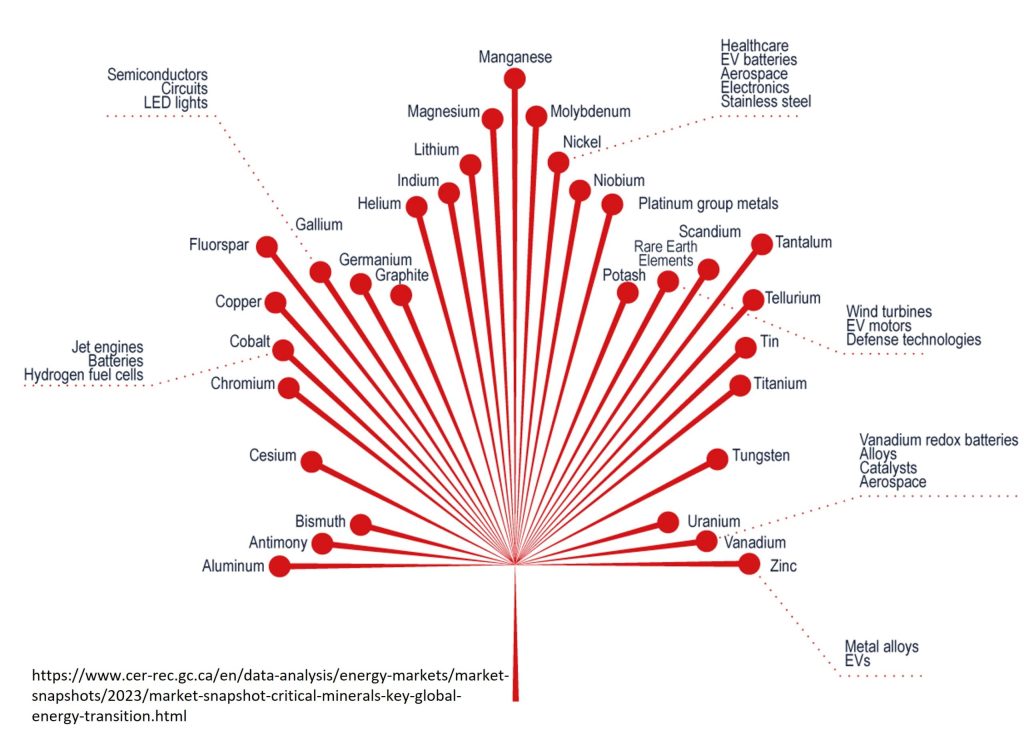

Canada’s 31 critical minerals, artfully arranged.

Canada has created a list of 31 critical minerals, with six (lithium (Li), nickel (Ni), cobalt (Co), graphite, copper (Cu), and REEs) listed as priorities. So far, federal support for critical minerals has come in the form of tax credits, funding for infrastructure, and the establishment of the $15 billion Canada Growth Fund.

Is it Working?

While it sounds like there’s plenty of funding to go around, much of this has been devoted to projects further up the supply chain; mines may actually be more likely to get funding from the American critical minerals program. Announcements of new battery factories and EV plants in Canada have been highlighted as successes, but these are low-hanging fruit: factories only take months to a few years to construct, they can be built anywhere, and they are generally popular. Unfortunately, they’re about as useful as a chair without legs if the underlying supply chains aren’t secure.

Canada has no shortage of critical minerals, but production of most of them has remained stubbornly low. Nickel production has actually decreased. Canada produces just 2% of global Li, none of which is processed domestically, despite having a sixth of global reserves. Almost everyone agrees on the problem: it simply takes too long to open a mine in Canada.

Despite the increasing need for Ni, Canada’s production has fallen significantly as old mines deplete their reserves and new ones fail to materialize.

Timeframes for mines to enter production are typically 12-15 years but may exceed 20. That’s a long time for investors to wait on a return for their investment, not to mention the risk of changing market conditions rendering a project unfeasible before it even gets started. The major James Bay and Whabouchi lithium projects were shelved for several years after their economics soured during their lengthy exploration and construction processes. While large, high-grade Li deposits were discovered in the area as far back as the 1960’s, none of them have reached production despite enormous investments in exploration and development since the late 2000’s.

To make matters worse, China has been accused of sabotaging competing projects by using its dominant position to manipulate markets, especially in the case of REEs. In recent weeks China has banned export of technology used in processing REEs, a move clearly designed to maintain its dominance in this area. While Canada has extensive experience processing more established minerals such as Ni, Cu, and uranium, the expertise to economically refine REEs and Li in North America is in its infancy.

Change on the Horizon?

Developing a mine will never be quick; the government hopes to reduce timeframes to 5-7 years. The main issue cited in delays is Canada’s lengthy, complicated review process. Canadian mines are regulated by dozens of different agencies, any one of which may take years to approve or block a project. While mining in Canada falls primarily under the control of the provinces, mines may also impact federally-regulated waterways, endangered species, indigenous communities, and more, meaning they have to pass multiple provincial and federal reviews. The Canadian process is widely considered one of the most complex, lengthy, and inefficient permitting systems in the world.

Recognizing the problem, the federal government has promised to streamline the process. How that will work, exactly, isn’t clear. The strategy calls for a ‘one mine, one approval’ system, where redundancies are eliminated and reviews are coordinated so that mines only require one regulatory review. How this would work in practice is unclear, as it would effectively require the provinces and the federal government to either work together seamlessly or cede a significant amount of power to the other. Neither seems likely anytime soon.

What any effective strategy really needs is to be clear and easily understood. One review will be just as inefficient as many if no one knows how to navigate it. Ideally, the review process would begin as early as possible, so that these hurdles can be cleared before construction is ready to begin. The major impacts of a mine tend to be fairly obvious once the basic character of the deposit is known; a more nimble, transparent review process that prioritizes identifying issues and returning feedback as quickly as possible would go a long way.

Indigenous reconciliation also features heavily in the critical minerals strategy. While indigenous communities have often borne much of the cost and seen little of the benefit of mining, this is changing. Opening a mine without the support, or at least acceptance, of local indigenous groups is almost impossible today, and the industry increasingly understands that it must engage with them as early as possible. Some of the most successful projects are now indigenous led. Despite understandable concerns, indigenous communities also have much to gain: mining is one of the few industries which can bring high-paying jobs and much-needed infrastructure to otherwise isolated communities which have been largely bypassed by the modern economy.

In many ways the mining industry is haunted by its past. While the industry has come a long way from the days of our grandparents, many still view mining as little more than pillaging the Earth. Coverage of mining in media is almost universally negative, and neither the industry nor the government has done much to push back. These outdated perceptions mean miners have to start from square -1 when it comes to indigenous consultation and has also contributed to recruitment deficits. Many of the young professionals the industry needs to succeed simply want nothing to do with it.

A Global Perspective

Any sensible critical minerals strategy needs to acknowledge that while resource extraction is a zero-sum game, its impacts are not. Every mine that doesn’t open in Canada means another one has to be opened somewhere else, and there’s a very high chance that this somewhere else has far less stringent environmental and human rights protections. Not only is importing critical minerals a net loss for Canada’s economy; it’s likely to be a net loss for the world.

Take Ni for example. This critical mineral is an essential component of electric vehicle batteries as well as having many uses in defense, steel making, and other industries. Canada has some of the largest and richest Ni deposits in the world, particularly in the Sudbury area. Processing the sulfide ore from these magmatic sulfide deposits in old-fashioned smelters once produced so much air pollution that NASA used the wasteland downwind of the smokestacks to prepare astronauts for the moon. Since the 1990’s however, tougher environmental standards have seen the smelters replaced with modern, far less-polluting processing plants and contaminated areas remediated, allowing forests to steadily reclaim the moonscape.

The situation at the world’s largest magmatic sulfide deposit, Norilsk, Russia, couldn’t be more different. Norilsk’s minerals are considered so vital to the Russian war machine that the entire city is considered a strategic asset and is closed to outsiders. The city and the mines it supports were built in only a few years with forced labor, resulting in thousands of deaths. Lax environmental protections have allowed Norilsk’s soviet-era smelters to pollute freely for decades, earning the city the label of one of the most polluted, and depressing, cities on Earth. Life expectancy in Norilsk is ten years below the Russian average, and cancer rates are double. Rivers and snowfall occasionally turn blood red due to suspected chemical spills. While the smelter has promised to slash emissions, it’s not clear how much progress has been made. When soils downwind of smokestacks were found to be severely contaminated with heavy metals, the response was not to investigate remediation, but to investigate the profitability of mining the polluted soils.

Norilsk’s infamous ‘red river’ after a suspected chemical spill in 2016.

Nickel sulfide deposits only account for about a third of the world’s Ni, with the rest coming from laterite deposits which arguably have even worse environmental consequences. Laterites only form in tropical soils, meaning mining them often requires bulldozing swaths of the most biodiverse habitats on the planet. While processing laterite ore isn’t typically associated with air pollution, these ores are very energy-intensive to refine, and often require the use of highly toxic chemicals. Despite being brand-new, Indonesia’s massive Weda Bay Ni laterite project has already been linked to deforestation and human rights abuses, including destruction of rainforests supporting some of the world’s last uncontacted indigenous peoples. Absurdly, the energy needed to refine nickel for climate-friendly electric vehicles is coming from burning coal in Weda’s purpose-built power plant.

Weda Bay is majority owned by a Chinese company; the race for critical minerals knows no borders and no rules. If the rewards of winning, and the true costs of losing, it were more widely appreciated than perhaps Canada wouldn’t be so far behind. Far from shunning Canadian mining, people who want to see a positive change in the world should be getting involved.

Conclusion

Producing critical minerals in Canada is essential for ensuring national security, economic development, and environmental protection. The Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy recognizes this but is only a first step in solving persistent challenges in developing new mines in a timely and responsible manner. The work of creating a clearer, more efficient permitting process and building public trust will not be easy or quick, but it is critical.